Palette, paintbrush, watercolors, charcoal, pen and ink. Across the wide lunchroom table, Rachel Vortherms spreads out these tools of a nature journal keeper. The heavyweight paper in her sketchbook accepts wet paint with ease. She paints and inks over light pencil lines, and a pleasing circle of the moon’s phases emerges. Satisfied with her latest effort, Rachel flips back to autumn’s entries: brilliant plumage of chickens, a pileated woodpecker, and paper birch in fall’s colorful cloak.

Rachel will wrap up her Naturalist Fellowship at Dodge Nature Center in June. By then, she will have three seasons of journal entries that track not just phenological data—temperature, precipitation, bird migration—but also artistic renderings of observations made at Dodge.

Naturalist Fellow Rachel Vortherms paints the phases of the moon in her nature journal.

Naturalist Teresa Root, who coordinates the Fellowship, says these natural history skills are one of the four pillars of the yearlong experience. She guides the Fellows from their first day until graduation. She aims to give them an experience distinct from those offered by any other Minnesota nature center or environmental learning center.

Dodge’s Naturalist Fellowship is intended for college graduates with solid backgrounds in environmental education—and who want to build up their skills even more.

“We recognize that they already have teaching ability,” Teresa says. “We are just icing the cake.”

According to Teresa, the Fellowship was developed eight years ago to be different from an undergraduate internship in numerous ways. Fellows teach and learn every day, every week for a whole year—far more than a 15-hours a week, 3-month long internship can offer.

Considered essential members of Dodge’s team of naturalists, Fellows lead field trips for Pre-K through 12th grade students, after-school classes and outreach events. Teresa says Dodge could not serve nearly the same number of children and adults without Fellows’ contributions.

“It’s not just that we want Fellows—we need them.”

They care for and handle Dodge’s creatures, from reptiles to roosters. They feed and water farm animals—and yes, they muck out the barn.

“Having that responsibility for animals is huge,” says Fellow Siri Block. “That push to pick up the animal, clean it, practice holding the snake for an hour. It’s very challenging.”

With an undergraduate degree in biology, Fellow Ashley Johnson was drawn to Dodge to grow her hands-on skills too.

“I had the foundation, but didn’t have the application or the professional skills,” she says. “I appreciate all the extra education I receive here.”

Not only do they collect a biweekly stipend, but the four Fellows have housing right on nature center grounds. Siri says living on the property provides a deep sense of ownership and connection to the land—and “it’s magical to walk to work!”

Teach often, teach a lot

By the end of the year, Fellows will have taught a huge range of topics, from aquatic life to wilderness skills.

“For good reason Dodge is known as the place to learn to teach—because you are going to teach a lot,” Teresa says with a laugh.

Naturalist Fellow Ashley Johnson introduces elementary school students to kicksledding on the Farm Pond.

Before serving as lead teachers, Fellows cement not only their nature knowledge, but also behavior management skills. This is essential at Dodge (or any other nature center), in order to best serve learners from preschool to high school—plus adults, families, seniors, and people with disabilities.

“One thing we’re really proud of is training Fellows how to read an audience and adapt the lesson,” Teresa says. “How to meet people where they are.”

Fellows mirror and model Dodge’s team of naturalists, which Teresa calls “an exceptional teaching staff” with decades of experience under their belts.

What’s teacher training like for the Fellows? It’s outside, it’s hands-on—and it’s crammed with questions.

One afternoon in January, naturalist Jeff Boland leads the Fellows down a snow-packed path. Coming to a halt, he urges them to look up, down and all around.

Naturalist Fellows hike through Dodge's wintry woods, searching for animal tracks and signs.

“How many signs of animals can you see?” he says. “And who just heard that bird?”

The naturalists-in-training are quick to adopt Jeff’s suggested best practices. Ears tipped to the skies, eyes trained on the ground, pencils tallying every sign of animal activity.

“First rule of intelligent tracking?” he says. “Don’t step on the tracks!”

Jeff is modeling how to teach Animal Tracks and Signs, one of 30-plus field trip classes the Fellows will lead in their year at Dodge. Because animal signs appear and disappear every day, and vary over the seasons, he says this class is never the same twice. By sharing with other naturalists what they find on a given day—especially overt signs like prey kill sites, scat and animal homes—they can better route students within the expansive 110 acres of Dodge’s main property in West St. Paul.

Naturalist Fellow Siri Block inspects the snow-covered prairie for mammal tracks.

The training takes the Fellows to the prairie to burrow into the subnivian zone, the warm space under the snow where mice and voles overwinter. They cut into a gall to examine the insect larva within.

“We’re good ecologists, so we can’t waste that energy,” Jeff says. “Will anyone eat it?” (Rachel is up to the task.)

They pick up their pace, and the signs pile up: coyote, deer, and mice tracks; thorny gooseberry stems bitten down by rabbits; a tree trunk polka-dotted with pileated woodpecker holes; a predacious water beetle caught in the minnow trap.

Ashley and Rachel pluck a lacy seedpod that overhangs the trail. In their ungloved hands, they dissect it, swapping observations: “It looks like a loofa! A lantern! No— origami!”

One can picture them having just the same excited conversation with first graders on a field trip. They get the message that maybe it’s less important to know the plant’s name (they’ll later learn its wild cucumber), than it is to be curious.

“You’re not expected to be an expert,” Jeff assures them. “It’s about getting students to notice.”

Back inside a warm classroom, Jeff asks the Fellows the question they will soon be asking of young students: “What’s our data?” Five types of tracks, three scat, eight homes, four feeding sites—all found within an hour.

Search, perch and research

Even in their downtime, Fellows show interest in improving their knowledge of the natural world. They quiz each other on winter constellations, work through dichotomous keys to ID trees, and sort skulls and skeletons. They hand make recycled paper from a slurry of scraps. They pepper the Dodge staff with questions over the lunch hour.

“There’s a lot of knowledge and desire to gain knowledge [at Dodge]," Rachel says. "Everyone welcomes what you know too. They want to hear it.”

“There’s a culture of curiosity and learning here at Dodge.”

Teresa has recorded scientific data and been an avid nature journaler for thirty years, so making it a requirement of the Fellows was a very logical way to boost their observational skills.

“It’s not about becoming polished artists or having finished works of art,” she says. “It’s about ‘What do I notice about this animal in this moment?’”

Fellows choose a sit-spot at one of Dodge’s four properties. They return there at least once a month, silent and still, engaging all five senses, drawing in their journals. Among their observations this winter? There are often no other boot tracks around their sit-spots. These nature center nooks are theirs alone.

Julia Pedersen, left, Siri Block and Rachel Vortherms test out snowshoes on Dodge's snowy trails.

In the yard of the Fellows’ house, Rachel positioned a trail camera. In the grainy gray images, she caught what may not otherwise be observable: coyote, wild turkey, herds of white-tailed deer.

And when the snow starts to melt, the Fellows will put phenology on their breakfast plate. By tracking temperatures, they’ll know when days are above freezing, and nights are below. Then they’ll tap the maple trees in their backyard, and feast on pancakes and syrup in their communal kitchen.

Know what it is to be a naturalist

As their mentor, Teresa keeps an eye towards Fellows’ futures. She helps them write cover letters, and hone their resumes to best reflect their responsibilities and accomplishments. She tracks where and what her 25-plus Fellows have gone on to do after leaving Dodge. Most are environmental educators, some landed at preschools, and one has worked as a museum professional.

“We want Dodge to give you depth and breadth so you’re ready for that first job,” she tells her current class.

Fellow Julia Pedersen considers her experiences at Dodge as complementary to her pursuit of a master’s degree in environmental education at Hamline University.

“I was attracted to Dodge because it’s urban, it’s close, and it offers a diverse catalog of classes to teach,” she says.

The other Fellows echo her.

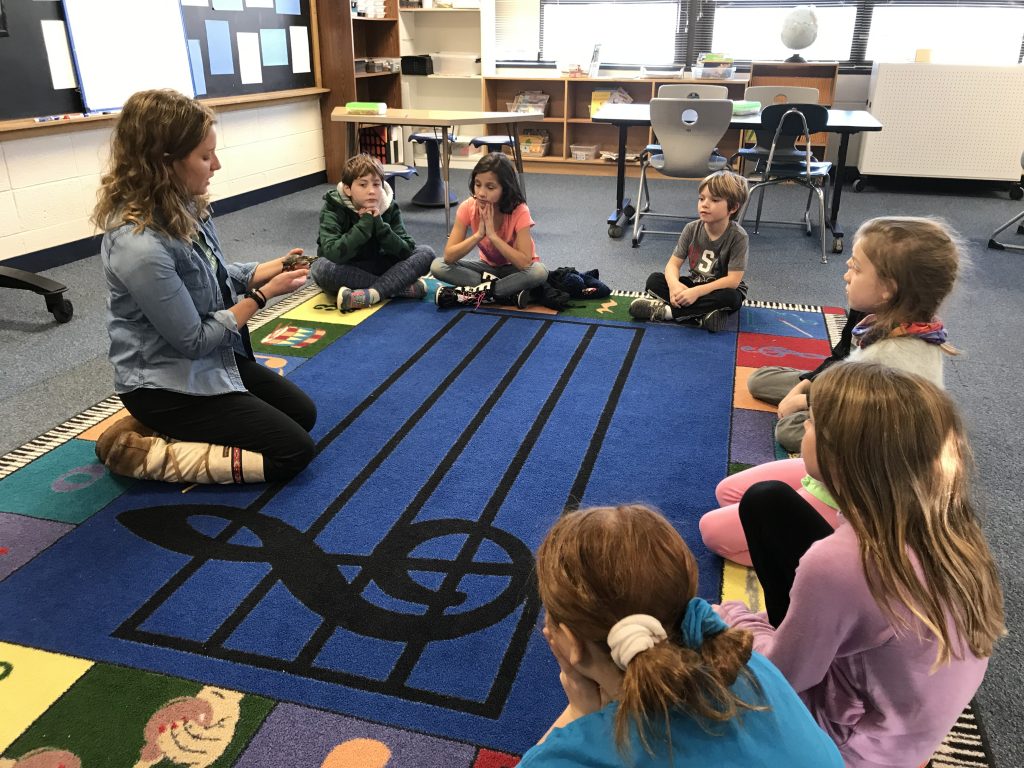

Naturalist Fellow Siri Block shares a Painted Turtle with students in an after-school program at Mendota Elementary in Mendota Heights.

“What drew me to the experience was the diverse audiences,” Siri adds. “I wanted to link kids to the idea that there is wilderness in the city. I believe that nature is wherever you encounter it. Dodge is a direct manifestation of that.”

“Yes, exactly! Nature experiences don’t need to be remote,” Rachel chimes in.

Fellows are encouraged to follow their interests wherever the trail leads. They are researching rain gardening to present a spring session of O.W.L.S., Dodge’s monthly education program for seniors. Siri will don a beekeeping suit this spring and care for Dodge’s 450,000 honeybees. After Rachel expressed an interest in the orienteering curriculum, she was tossed a rangefinder and told “Go for it!”

By assigning the Fellows “other duties not specified,” Teresa builds their adaptability and creativity. Fellows have created cattail mazes, carved jack-o'-lanterns, and designed a mini golf course out on the icy pond.

Dodge's 2019-2020 class of Naturalist Fellows in the prairie on the Main Property in West St. Paul.

She wants them to understand Dodge as a nonprofit organization, too. Wherever the Fellows are employed next—another nature center, an elementary school, public lands—they’ll need to have a grasp of staffing, budgeting, fundraising, and meeting one’s mission. Jason Sanders, Dodge’s executive director, will walk them through the basics.

To further ensure a bright future, Fellows are given memberships in the Minnesota Naturalists' Association, and the opportunity to attend professional conferences.

“Having access to that larger community of naturalists is wonderful,” Rachel says. “We benefit from Dodge’s strong relationships [with other environmental organizations], and we meet many potential employers.”

Having just graduated from the University of Minnesota Duluth in May 2019, Rachel values the opportunity to “dip my toe into being a naturalist” in the supportive, family-like environment at Dodge.

“Every single person here loves to learn,” she says. “I knew it was a place I would thrive in.”

Interested in being a Naturalist Fellow at Dodge Nature Center?

Visit the Naturalist Fellowship page to learn more. For more information, email Teresa Root, Naturalist Fellowship Coordinator, [email protected].