Success in Dodge’s Signs of Spring contest rests less on athletic ability, luck of the draw or the spin of a wheel. Unlike a basketball tournament or pull tabs or a television game show, this competition depends on a contestant’s observational skills and attunement to the natural world.

Dodge naturalist Teresa Root developed the contest to honor a feeling shared by many Minnesotans in early March: “You’re so tired of winter, and really looking forward to spring.”

She got the idea for Dodge’s contest when she stumbled upon the website of an East Coast-area nature center. They offered a competition in which people guessed the week in which a sign of the season would occur.

“That seemed much more realistic to me than guessing by day,” she said. “It was like a cool nature scavenger hunt, only you don’t collect anything physical.”

Painted Turtles sunbathing on the Farm Pond.

Dodge’s contest kicked off at the start of meteorological spring in 2012. Teresa began with a list of 30 signs, broken down by categories: amphibians, birds, insects, plants, reptiles, and weather (and one fungus).

Teresa has since honed the list to 25 signs and pushed back the contest by a week.

“March 1 didn’t really work, because nothing is happening quite yet,” she says. “Though sometimes spring happens sooner than you think, like when it was so warm in 2017.”

When will American toads trill? Violets bloom? Ice disappear from the Farm Pond? Contestants mark entry forms with their educated guesses on which week each of these signs (and 22 more) will be spotted by Dodge naturalists. Teresa says you can pick more than one sign per week—but only one week per sign.

Violets in bloom.

When the contest ends on May 31, the three people with the most correct guesses win prizes.

Though Teresa has been at the helm of the contest for its duration—and has all the years of compiled data—she says uncertainty is the rule of the game.

“Part of why I love it is you can have a sense for when things will happen, but you never know," she says. “There’s no such thing as dead-on consistency.”

Guess for success

But one person has certainly been more consistent than most, and won the contest several times.

Tony Ernst is a computer programmer who’s always had a strong interest in science and the natural world. He lives just a mile north of Dodge’s main property, and came here for training as a Minnesota Master Naturalist volunteer. On the prairie, he’s helped with restoration work, uprooted invasive species, and collected native plant seeds.

“Whenever I want to get outside, I just head down to Dodge,” he says. “I explore, I don’t stay on trails. And I’m still finding new things after coming here for decades.”

Common Sanddragon dragonfly on the boardwalk.

Tony is an active contributor to iNaturalist, a website and app for recording and sharing nature observations. He has tracked down every species of wild orchid in Minnesota (including Loesel's Twayblade, Liparis loeselii in the vicinity of Dodge). He’s racked up many more unusual IDs by visiting Minnesota Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), which preserve native plant communities and rare species.

In the summer, Tony volunteers as surveyor for the Minnesota Bee Atlas, a University of Minnesota research project documenting the range of 22 bumble bee species. As a surveyor, he follows a specified route and protocol, but also takes time to see what’s pollinating the flowers at Dodge. That’s where he spotted the endangered state bee of Minnesota, the rusty patched bumble bee, Bombus affinis.

“I always stop and look at Monarda [bee balm] because there’s always something interesting going on there,” he says.

For more than twenty years, his family has grown vegetables in a community garden plot at Dodge. A bounty of garlic is already in the ground, ready to sprout in spring’s warmth.

Community garden plots on the Main Property.

Tony, too, is awaiting the start of spring–when he can submit his perennial entry in Dodge’s Signs of Spring contest.

Despite his winning entries, he demurs at being called a phenologist, someone who studies recurrent events and happenings in nature, like migration, hibernation, flowering, fruiting and leaf-fall.

“I haven’t been recording data for decades,” Tony says. “But I do take a lot of photos.” He runs a Dodge Nature Center group on Flickr, a photo sharing site (and welcomes new members). Date stamps on photos—favorite flowers in blooms, monarchs on the prairie, wood ducks on the water—help him see trends and divergences year to year.

Monarch Butterfly resting on a Brown-eyed Susan.

He encourages others to try their hand at the Signs of Spring contest—but he preaches realism, too.

“The first year is hard,” Tony says. “But the more years you do it, the easier it is. You keep tweaking your guesses.”

He credits some of his winning to fine-tuning his entry form every year. He’s deduced that migrating birds are the most dependable in when they show up; soil temperature and snow cover varies much more and affects when plants will sprout. But most importantly, he says success depends on paying attention year-round to sights, sounds and happenings in the natural world.

You don’t even necessarily need to come down to Dodge to spot these signs, he says. Many of them—dandelions blooming, maple tree seeds, mosquitoes—are likely to be in your own yard or neighborhood.

“Inherently interesting”

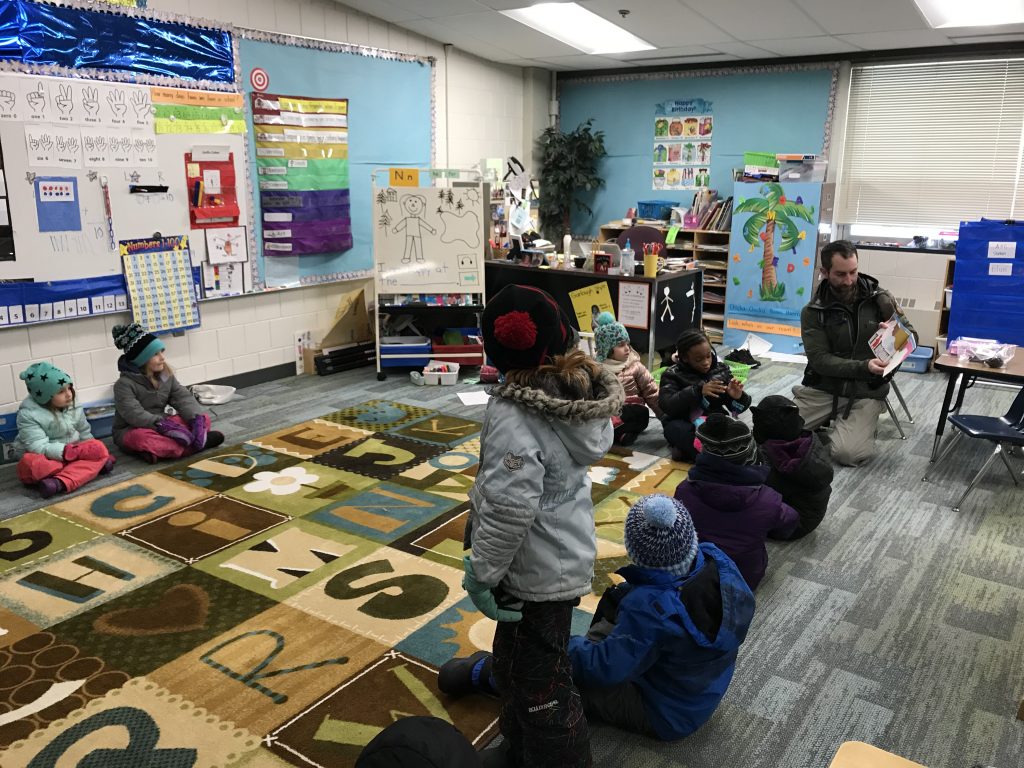

Tracking the signs of the seasons isn’t just for adults. When Dodge naturalist Jeff Boland designs curriculum for the kindergartners through fourth graders he teaches at Garlough Environmental Magnet School, phenology is a no-brainer part of the plan.

“Kids are naturally curious,” Jeff says. “Especially if they have been inside all day!”

Dodge naturalist Jeff Boland teaching at Garlough Environmental Magnet School.

He works with the lead science educator in the building to meet learning targets and visions for each grade level. For example, third graders need to identify changes in our world.

“Phenology plays into that really well,” Jeff says.

So, he gets students outside, walking through the forest and across the frozen pond—a source of anxiety for some. Jeff tells them that the DNR says ice must be at least 4” thick to support foot traffic. Then he has them auger into the ice to discover a reassuring (and phenological) fact: In the depth of winter, the ice is 18” thick.

Fourth graders start every class working in their nature journals, an indispensable tool of phenologists. They record temperature, cloud formations and wind patterns. They make observations, sketch and label their drawings.

“Kids are closer to the ground, so they often notice the cool things first,” Jeff says. “For them, nature is inherently interesting.”

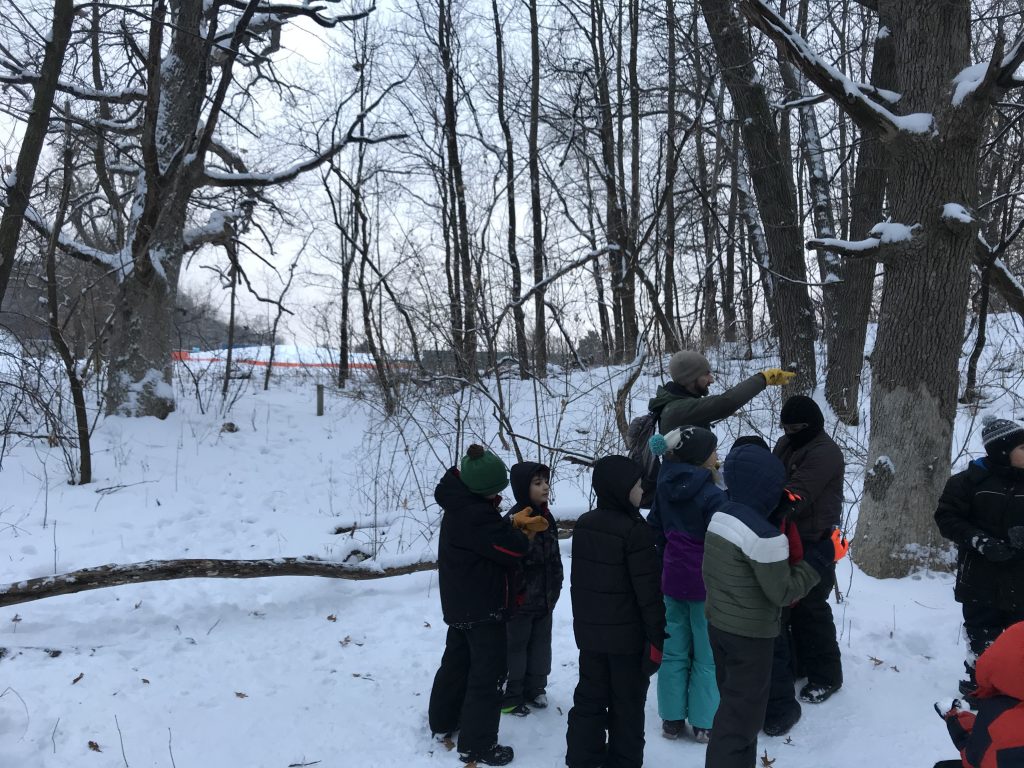

Dodge naturalist Jeff Boland teaching winter tree identification.

He finds most kids are very familiar with the facts and threats of climate change. By recording phenological data, they can compare and contrast today’s conditions to those in the past. Jeff will ask them: Is the temperature you recorded today typical for this date, or atypical?

“I want them to know everyone can make observations like a scientist.”

As Dodge eases into spring, Jeff is teaching his students winter tree identification—a tough task without large, lobed leaves as clues. He shows them the trick to IDing a maple tree—opposite branching—and gives them one minute to find one and have a friend check their work. The next unit he teaches, naturally, is maple syruping. When these budding phenologists try tree sap, they will identify one very sweet sign of spring.

Tips and tricks

Still feeling daunted by the Signs of Spring contest? Teresa has some words of wisdom.

“Red-winged Blackbirds are always first, and monarchs are last,” she says. “Sometimes monarchs haven’t even shown up by the end of the contest.”

Red-winged Blackbird perched on a cattail.

For amphibians, “spring is all about reproduction.” They need ice off the pond before they sing their songs and lay eggs. “At peak, you can hear them from the parking lots,” Teresa says. “Kids will think its crickets. I tell them you need to listen, because frogs and toads go quiet as soon as you get close.”

Most years, no sign is glimpsed (or heard) until the end of the third week of March. There’s a freebie this year, too. The Twin Cities hit 61° F on Sunday, March 8—before the contest even started. That means everyone already got one correct.

Teresa sends out weekly emails about signs as they are spotted at Dodge. She hopes the contest inspires participants to spend the spring deepening their observational abilities.

“Just sit in a chair in your backyard, slow down, take time, really notice,” she says.

And one last note to boost competitors’ confidence: Teresa says you may only need 4 or 5 correct to win the contest.

Attendees at Rock the Barn 2019 enjoy a cool spring day on the Farm Pond.

Entry forms are due March 9, 2020 by 4 p.m.